- Blog

- Climate & Energy Justice

- The “Rainforest Chernobyl”: Will U.S. Investment Treaty block justice for Amazonian People?

The “Rainforest Chernobyl”: Will U.S. Investment Treaty block justice for Amazonian People?

Donate Now!

Your contribution will benefit Friends of the Earth.

Stay Informed

Thanks for your interest in Friends of the Earth. You can find information about us and get in touch the following ways:

Who should pay to clean up what has been called the “Rainforest Chernobyl” in the Ecuadorian Amazon? Why are the people of the rainforest who suffered the most not represented directly before the international investment tribunal that may decide the question? Is it U.S. policy to favor the financial interests of multi-national corporations over people and the environment in such disputes?

The answers to these questions may be found in the case of Chevron v. Ecuador. The case is under consideration by an international investment tribunal convened under the terms of the U.S.-Ecuador Bilateral Investment Treaty. The tribunal has created a major international controversy in two dramatic moves favoring Chevron over the past two weeks. It has claimed jurisdiction to consider Chevron’s claim that the U.S. BIT was violated by an Ecuadorian court decision that the oil company must pay for the clean-up. And, it has gone so far as to order the government of Ecuador to suspend enforcement of the judgment against Chevron in any court in the world.

Friends of the Earth is dismayed by the tribunal’s actions, but regards the underlying problem to be the flawed model for U.S. BITs and investment chapters in free trade agreements. The U.S.-Ecuador BIT is typical. It favors the profits of big oil companies and other wealthy international investors. The overreaching of the Chevron tribunal should be a warning to negotiators from the United States and other Pacific countries as they meet in Melbourne, Australia in the coming week to fashion a Trans Pacific Partnership trade agreement.

Facts

In the 1960s, Chevron’s corporate predecessor, Texaco, discovered oil under the rainforest of eastern Ecuador. Texaco, leading an investment consortium, was the exclusive operator of the huge project. The company sank wells and pumped oil across the Oriente region. In 2001, Texaco’s operation was absorbed by Chevron, which inherited the legal liabilities.

The indigenous people who live in Oriente say that over a more than twenty-year period up to 1990, Texaco intentionally dumped billions of gallons of poisonous waste onto the soil and surface waters and abandoned hundreds of unlined waste pits that leaked toxins and heavy metals into the groundwater.

The indigenous people and poor settlers of Oriente suffered an epidemic of cancer and other illness that they say resulted from Texaco’s dumping. Death, miscarriages, and birth defects cut a swath through communities, threatening some indigenous groups with extinction. The destruction of the rainforest environment, noted for its biodiversity, was similarly devastating.

A court-appointed independent expert in Ecuador found that damages from the dumping amounted to $27 billion. Legal consultants to the indigenous community have called the destruction in an area the size of Rhode Island a “Rainforest Chernobyl.”

Litigation history

On February 28, an international investment tribunal accepted jurisdiction on the merits in a lawsuit brought by oil giant Chevron against Ecuador. Chevron alleges that it cannot get a fair trial in Ecuador. This is only the latest chapter in a long-running legal dispute over who is financially responsible for the environmental and human rights disaster in the Amazon rainforest.

The decision on jurisdiction follows the tribunal’s February 17 order to the government of Ecuador to suspend enforcement of judgments by an Ecuadorian provincial court in the suit brought by indigenous groups and others against Chevron. The order applies to enforcement actions sought both “within and without Ecuador” — including the United States.

These controversial actions of the Chevron tribunal have their origins in decades of litigation. Since 1993, indigenous groups and others living in the Amazonian region of eastern Ecuador have been fighting in Ecuadorian and U.S. courts against Texaco and Chevron.

The original 1993 suit was filed in a U.S. federal district court in New York on behalf of 30,000 residents of Oriente. Texaco argued that the U.S. suit should be dismissed and that the issue should be heard in the courts of Ecuador. In 2001, a U.S. federal judge agreed, and dismissed the case. In 2003, the plaintiffs filed suit in Ecuador. Finally in January of this year, an Ecuadorian court ratified an $18.2 billion judgment against Chevron, finding it responsible for the environmental and public health costs of the dumping. Chevron could have cut its liability by $8.5 billion if it had agreed to apologize for its actions, but the company refused to do so. Reportedly, Chevron no longer has assets in Ecuador that could be seized. So, the Amazonian plaintiffs only recourse would be to try to collect the award of damages in the United States or someplace else abroad.

The U.S.-Ecuador BIT

The U.S.-Ecuador Bilateral Investment Treaty is largely based on the model of the North American Free Trade Agreement’s investment chapter. Big oil, mining multinationals, and giant agribusiness have demanded NAFTA-style investment provisions in subsequent BITs and free trade agreements that would allow them to sidestep national legislatures and courts.

NAFTA-style investor protections provide an effective enforcement tool: the assessment of money damages. Such damage awards can be large enough to break public budgets of countries like Ecuador. The fear of such ruinous judgments can force a developing country to settle unjust investor claims and to back away from protecting the environment.

Under the U.S.-Ecuador BIT and other NAFTA-style investment agreements, substantive and procedural rights of “property” are far more broadly defined than in U.S. constitutional law or the legal practice of nations around the world, generally. This potentially allows regulations or court decisions that incidentally thwart multinational corporations’ expectations of future profits to be treated as if they were a government “taking”—for example, when a government takes real property to widen a highway, requiring it to pay the owners fair value.

The U.S.-Ecuador BIT like NAFTA departs from the usual practice in international law for claims to be arbitrated on a government-to-government basis. By allowing investors to sue directly, it puts multinational corporations and wealthy investors on the same level as nation-states. No similar procedural rights are provided to ordinary citizens, such as the indigenous peoples of the Amazon in this case.

The most brazen action by the Chevron tribunal in February was issuing an injunction ordering the president, the parliament and the courts of Ecuador to suspend enforcement of the court judgment against the oil company in any court, foreign or domestic. Rather than simply seeking money damages as BITs unfortunately clearly authorize, multinational investors around the world are asking investment tribunals to issue injunctions even on questions of public policy. This would amount to a breathtaking aggregation of power by the tribunals. In its fight against public health measures regulating cigarette package labels, Philip Morris is asking for an injunction against Uruguay. And, Renco, said to be one of the worst polluters in the world, is asking a tribunal to take similar action against Peru.

Recently-adopted U.S. BITs and free trade agreements have sought to curb such injunctions, but earlier U.S. BITs, including the one with Ecuador, do not address the problem. To make matters worse regardless of the “good intentions” of recent U.S. BITs, clever corporate lawyers might argue that BITs are “self-executing”: in other words, that domestic courts could issue injunctions or judgments based on BITs, not domestic law.

The reaction of Friends of the Earth

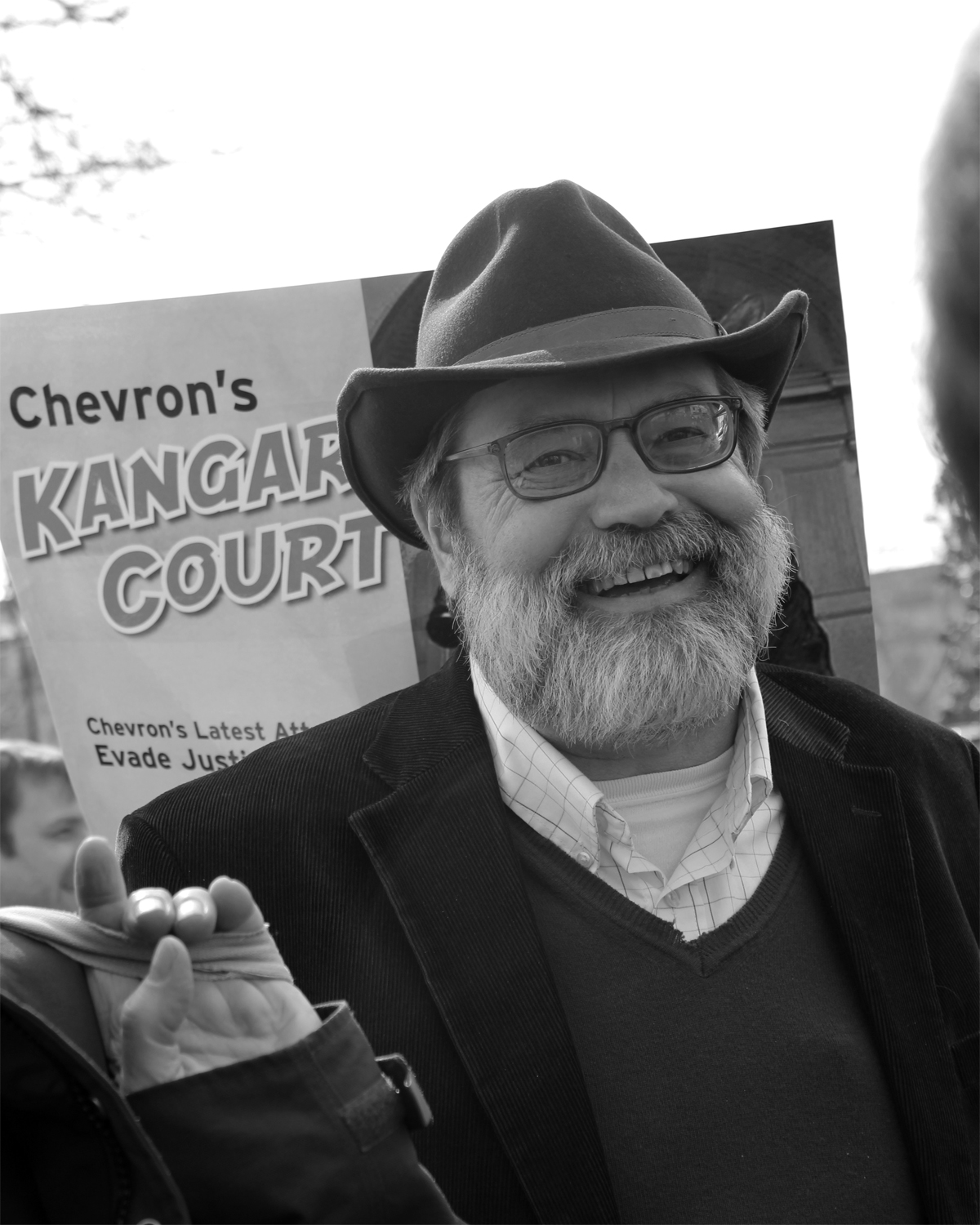

In response to the international investment tribunal’s decision, Bill Waren, trade policy analyst, had the following statement:

The indigenous peoples of the Amazon only seek simple justice in response to one of the greatest environmental catastrophes of our time. It is a scandal that U.S. investment agreements allow tribunals to second guess the decisions of democratic governments and national courts in this way.

What would the response be in the United States, if an international investment tribunal ordered the president, the Congress, and the courts to suspend enforcement of a lower court judgment, regardless of whether they had the authority to do so under the U.S. Constitution? What would be the response of the American people to an international tribunal deciding to take jurisdiction in a case like this?

The Chevron tribunal’s actions will energize the global movement to eliminate the system of investor-state tribunals established by bilateral investment treaties and trade agreements. As Trans Pacific Partnership trade negotiations move forward in Melbourne in coming days, the objections of the Australian people and others to proposed investment provisions that create a special “court” to serve the interests of international capital will be heard.