- Blog

- Forests

- False Climate Solutions

- A glimpse at Brazil reveals the big REDD problems that California’s Tropical Forest Standard fails to address

A glimpse at Brazil reveals the big REDD problems that California’s Tropical Forest Standard fails to address

by Chris Lang, REDD Monitor The Challenge of California’s Tropical Forest Standard

Donate Now!

Your contribution will benefit Friends of the Earth.

Stay Informed

Thanks for your interest in Friends of the Earth. You can find information about us and get in touch the following ways:

With the release of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change special report this week that explores the impacts of 1.5°C global warming, the heat is on to continue doing everything we can to address the climate crisis. But not all climate solutions are created equal.

Within environmental advocacy circles, a debate rages about the relative merits of radically powering down through measures like keeping fossil fuels in the ground and drastically curbing demand for deforestation-driving commodities like palm oil, versus solutions that create market incentives such as “payments for ecosystem services.”

As was made clear during the Governor’s Climate Action Summit in September, California is, by-and-large, choosing the latter route. Over the next six weeks, California decision-makers will be reviewing one such payment for ecosystem services policy — a long-talked about approach that will monetize tropical forests as a sink for California’s climate emissions.

We believe this is a very bad idea. Following is a recent article from the site REDD Monitor that raises some of the key concerns.

– Jeff Conant, Senior International Forests Program Director, Friends of the Earth United States

On 5 September 2018, the California Air Resources Board released a draft California Tropical Forest Standard. A 191-page Draft Environmental Analysis was released on 14 September 2018. A public meeting will take place on 15 November 2018, and the California Air Resources Board is inviting comments on the Environmental Analysis before 5 pm on 29 October 2018.

The draft California Tropical Forest Standard is riddled with problems.

The most obvious problem is that this is a carbon trading mechanism. The best that we can hope for from any carbon trading scheme is zero emissions reductions.

One ton of emissions theoretically avoided from reduced deforestation is cancelled out by one ton of emissions from burning fossil fuels. At its best it’s a “zero sum game”, as the then-chair of the Clean Development Mechanism Executive Board, Lex de Jonge, noted back in 2009.

100 years of permanence?

But even if we assume that the carbon calculations are accurate, that the baseline wasn’t fiddled, that the monitoring of deforestation is accurate, that deforestation won’t increase elsewhere, and that a genuine process of free, prior and informed consent was carried out before REDD was implemented (none of which are reasonable assumptions to make), we then have to hope that the forests remain standing for the next 100 years.

The draft California Tropical Forest Standard includes the following definition of “permanence”:

“Permanent” means that emissions reductions resulting from efforts to reduce tropical deforestation and/or degradation must not be reversed and must endure for at least 100 years.

The definition of permanence in the draft California Tropical Forest Standard points out that “it is not necessary to monitor the permanence of individual trees”, but “it is necessary for the jurisdiction to annually stay below its crediting baseline to maintain permanence.” For at least 100 years.

The absurdity of this idea is highlighted by the current situation in Brazil — the country that is often highlighted as a REDD success story. A look at the political reality in Brazil, as opposed to the hoped for changes that REDD proponents are clinging desperately on to, reveals a dire situation.

Brazil: Elections and deforestation

Presidential elections are to be held in Brazil this week. For most of the 13 presidential candidates, protecting Brazil’s rainforests is not even on the agenda.

The far-right nationalist Jair Bolsonaro, of the Social Liberal party (PSL), is currently ahead in the polls. When he announced he was running for president, Bolsonaro spoke about taking Brazil out of the Paris Agreement.

Bolsonaro is also in favour of opening up indigenous peoples’ protected areas to development such as mining and hydropower dams.

A large number of Brazil’s legislators have close contacts with agribusiness. This bancada ruralista, a group of large landowners and businessmen, have backedplans to reduce Amazonian protected areas, weaken legislation, and undermine indigenous peoples’ rights, and labour rights.

A recent post on Illegal Deforestation Monitor highlights the record of the bancada ruralista:

It has pushed for approval of the PEC 215, a constitutional amendment that would strip the executive branch of its powers to demarcate indigenous territories and place them exclusively with congress, a move that would enhance the ruralistas’ ability to shape indigenous policy. FUNAI, Brazil’s federal agency for the protection of indigenous peoples, has vocally opposed PEC 215.

In addition, the ruralistas were a major force behind President Michel Temer’s decree in 2017 granting amnesty to illegal deforesters and the 2016 decreereducing the size of the Jamanxim National Forest, which also let land grabbers and deforesters off the hook. In March 2018, the ruralistas celebrated a further amnesty, this time granted by a Supreme Court ruling that upheld the 2012 New Forest Code, which essentially pardoned acts of illegal deforestation committed before 2008. The agribusiness lobby has also been successful in its push for drastic cuts to Brazil’s environmental budget, with resources destined to FUNAI, IBAMA — the country’s environmental law enforcement agency — and the Environment Ministry cut by over 40 percent over the past two years.

The ruralistas do not exist in isolation. A new report by Amazon Watch documents the commercial links between agribusinesses in Brazil and European and US companies. The report states that,

Much of the political and economic power that enables the ruralista agenda is upheld by global traders, consumers, and financiers. European and United States businesses that purchase from and finance ruralista businesses therefore enable them to reshape Brazil’s socio-environmental landscape to our collective detriment.

Increasing deforestation in Brazil

While REDD proponents are keen to explain that Brazil’s success in reducing deforestation was a result of REDD, Philip Fearnside of the National Institute of Amazonian Research (Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia, INPA), argues in a 2017 paper that the real reason was commodity prices:

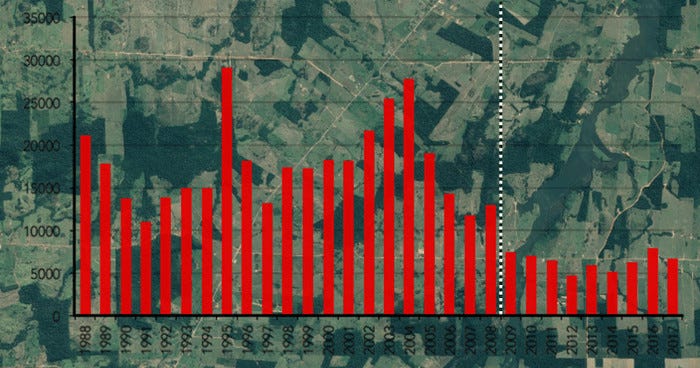

Deforestation rates have gone up and down over the years with major economic cycles. A peak of 27,772 km2/year was reached in 2004, followed by a major decline to 4571 km2/year in 2012, after which the rate trended upward, reaching 7989 km2/year in 2016 (equivalent to about 1.5 hectares per minute). Most (70%) of the decline occurred by 2007, and the slowing in this period is almost entirely explained by declining prices of export commodities such as soy and beef.

Norway’s US$1 billion in results-based payments for Brazil was announced in December 2008 (that’s the dotted line on the graphic below). Between 2009 and 2014, when most of the Norwegian money flowed to the Amazon Fund, deforestation remained pretty much stable.

Since 2014, deforestation in Brazil has been going back up.

Between August 2017 and May 2018, deforestation in the Amazon basin increased by 22% compared to the previous year, according to figures from Imazon. In the same period, forest degradation increased by 218%.

In June 2018, deforestation reached an area of 1,168 square kilometres — the highest monthly area since Imazon started monthly deforestation reports in April 2007.

Increasing violence in Brazil

In 2017, according to a report by Global Witness, 57 land and environmental defenders were killed. That makes Brazil the deadliest country in the world for people defending human rights and the environment. Agribusiness drives more killings than any other industry.

In 2017, United Nations rapporteurs sent two letters to the administration of Brazilian president Michel Temer. The first letter warned of threats to human rights activists in Minas Gerais state. The second letter condemned the record number of environmental defender killings in Pará state.

The Brazilian government simply ignored both letters.

As Amazon Watch points out, ignoring this type of warning, “creates a climate of impunity that paves the way for new acts of violence and intimidation”.

Global Witness observed a rise in multiple killings of land and environment defenders, and Brazil saw three “horrific massacres”, during which 25 defenders were killed.

REDD is not necessarily a driver of violence in Brazil. But REDD does nothing to address the power imbalance between agribusinesses and their political backers on one side, and indigenous peoples, quilombolas (descendants of Afro-Brazilian slaves), and small-scale farmers on the other.

Opposition to REDD in Acre

In 2010, the governors of California, Acre, and Chiapas (Mexico) signed a Memorandum of Understanding aimed at creating a REDD carbon credit system between the three states. Seven years later, indigenous peoples and environmental organisations in the state of Acre put out three letters or statements opposing REDD:

Suruí REDD project suspended

The Suruí Forest Carbon Project started in 2009. It received support from a wide range of organisations, including: Forest Trends; Google; the Brazilian Biodiversity Fund (Funbio); The Institute for the Conservation and Sustainable Development of the Amazon (IDESAM); The Etnoambiental Kanindé Defense Association; Amazon Conservation Team (ACT-Brasil); The Katoomba Group; software company Rhiza; and Trench, Rossi and Watanabe (an associated firm of Baker & McKenzie).

For REDD proponents, this was one of the most important REDD projects anywhere on the planet. The pro-REDD website Ecosystem Marketplace has written about Almir Suruí and the Suruí Forest Carbon Project dozens of times.

But the project faced pressure from illegal loggers. In 2012, Almir Suruí, the Suruí chief, wrote an open letter asking for “urgent action” from the authorities to help stop logging in the Suruí territory. Several more letters from the Suruí followed, but the reaction from government agencies was minimal.

When deposits of gold and diamonds were discovered on the Suruí’s territory in 2014 and 2015, deforestation increased as illegal miners moved onto the land. In 2016, Almir Suruí issued a “cry of alarm”. In it he wrote that mercury and cyanide had been found in three of the rivers in the Suruí territory because of the miners, and that, “Every day, 300 trucks leave our territory filled with wood”.

Last month, the Suruí Forest Carbon Project was suspended indefinitely.

REDD isn’t working

Of course, it would be wonderful if the current situation in Brazil were to change for the better. But the sad reality is that California’s proposal to include REDD credits in its cap-and-trades scheme does not include a mechanism for improving anything.

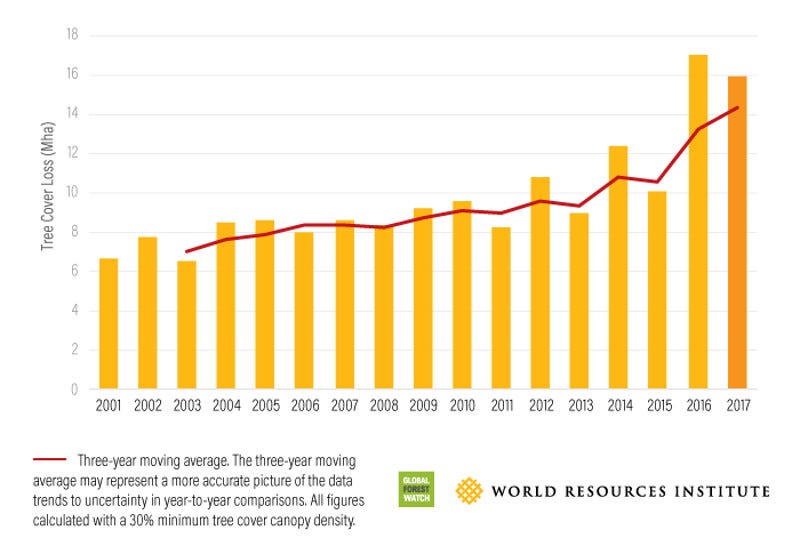

REDD has existed for the past ten years. But the results are not good. Tree cover loss in the tropics has increased steadily over the past decade, as this graph from Global Forest Watch indicates:

A recent paper published in Conservation and Society looks at “Actually Existing REDD” based on the authors’ own ethnographic research in Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam, and an extensive review of similar REDD studies globally.

The authors write that,

Our review and synthesis reveal that there are fundamental constraints to REDD+, which must be addressed if UNFCCC aspirations under the Paris Agreement are to be realised.

They found that local communities were “confused” about REDD, despite the processes of free, prior and informed consent that project developers had carried out. Financial benefits were often not delivered.

The authors found that the processes of land-use classification, mapping, carbon accounting, and demarcation tended to reduce complex socio-political processes to technical problems with technical solutions.

The authors found that there was strong evidence that REDD was not achieving its social and environmental goals. 90% of ethnographic studies that discussed REDD outcomes found social tension and conflict due to REDD, and ongoing forest clearance in the project area.

While substantial funding has flowed to REDD projects, it has gone mainly on the development of REDD bureaucracies, rather than to forest dwellers. The authors particularly highlight the risks of state-driven REDD implementation, arguing that it “provides no guarantee of emissions reductions, given potential issues with corruption, elite-backed resource grabbing, and new or exacerbated land conflicts.”