- Blog

- Forests

- Land Grabbing, Forests & Finance

- In the Peatlands of South Sumatra: A Tale of Two Villages

In the Peatlands of South Sumatra: A Tale of Two Villages

by Jeff Conant, senior international forests program manager

Donate Now!

Your contribution will benefit Friends of the Earth.

Stay Informed

Thanks for your interest in Friends of the Earth. You can find information about us and get in touch the following ways:

Where the Musi River snakes through the low, boggy peatlands of South Sumatra, the land and water flow into one another, the land green with growth and suffused with water, the water brown with the earth’s constant melting under pounding tropical rains. Along the river and its countless tributaries, houses built of faded meranti wood boards lean precariously on stilts with children splashing in the muddy river beneath. Water buffalo wallow in the grassy shallows and women in colored headscarves flash by on motor scooters where the road winds along narrow ancient dykes just inches above the flood.

In a nation afflicted with disasters, natural and otherwise, the ramshackle wooden homes whose legs sink into the Musi River’s floodplain appear frighteningly vulnerable. The villagers here must know what is only too apparent to the visitor — that the next cyclone will splinter their homes like matchsticks, the next typhoon carry them away to sea.

But until that storm hits, a slower watery disaster erodes the villages and claims lives here.

The palm oil industry is responsible for destroying some 24 million hectares of Indonesian rainforest since 1990, much of it through burning. But because huge areas of Indonesia’s vast peat bogs have been drained and dried out to make way for the plantations, the industry has also unleashed flooding in places like Sumatra’s wetlands — flooding that claims lands and lives in a way that is largely invisible. Used in snack chips, cosmetics, and biofuels, palm oil is a luxury in the west. And like so many of the luxuries that have come to be ubiquitous in the over-developed nations, it comes with a price that, unless you visit the source in the remote tropics, is scarcely imaginable.

After days of travel, I am welcomed into a house of weathered boards on stilts in a village called Belanti by a man named Mister Robanni Dulhakam, a local member of WALHI, Indonesia’s largest environmental organization. The inside of the house brings to mind others I’ve visited across the steamy tropics: gauzy family portraits hanging on nails in the board walls, prized possessions piled in aging cabinets with peeling varnish and a warmth of hospitality largely unmatched in my own country.

The palm oil industry has also unleashed flooding in places like Sumatra’s wetlands — flooding that claims lands and lives in a way that is largely invisible.

Women come and go quietly as Mister Robanni eagerly welcomes me in with a plate of fruit and a steaming cup of thick Sumatran coffee. After formal greetings and a cold bucket bath on a rickety lattice a few feet above the river, Mister Robanni takes me to meet his neighbors.

Years ago, the people of Belanti had two livelihoods: catching fish and farming rice, which they could make a good living selling in Palembang, the nearest city. But some 10 years ago a company made a deal with the district government to plant oil palm trees on 75,000 acres of peatland upstream from the village. In order to make their plantation, the company cut canals in the deep peat to drain the land and built earthen dykes to keep the water out. The water flooded the village’s rice paddies and the roads they used to get there. Now, large parts of what was the village and its farmland are underwater.

According to Mister Robanni, the company, Waringin Agro Jaya, exports its palm oil to Pakistan, but the details of the company’s operations are hazy. None of the villagers in Belanti will take jobs with the company. Shortly after the land was flooded, the villagers mounted a series of demonstrations; they went as far as to march to the dykes at the plantation’s boundary with picks and shovels to tear out the earthen dams and let the water flow — but their hand tools and determination proved useless against the company’s earthworks and political influence.

Although there’s more water than before, the change in the seasonal flow has altered the ecology and their fish harvest has been reduced from surplus to scarcity. With the rice paddies gone, they no longer grow and sell rice in the city, but buy it from neighboring villages. Mister Robbani explains the situation in Belanti Village as clearly as any economic analyst could: “No rice, no fish, no money.”

*

Mister Robanni walks me to the heart of the village, a collection of closely built houses whose pitched ceramic tile roofs and carved window frames are bent and worn by age and poverty and the punishing rains and brutal heat. A few feet from the road, ducks bob on the water in a mesh fish enclosure and narrow wooden boats called geteks pull at their lines as the river flows by in rapid current. After some minutes, a man arrives with a small two-stroke engine cradled in his arms, bolts it into one of the geteks and waves us over. We climb into the little boat, barely wider then my hips, and we set off downstream.

Steering out of the main current through a wooden weir and into a narrow canal, the village gives way quickly to a tangle of jungle: rambutan trees and coconut palms rising from banks of lily-green water, hyacinth and dark rushes. Occasionally a derelict board house leans into the trees, all but collapsed.

The canal opens onto wide, flat water with no current. We pass more derelict houses — some on the muddy banks, others standing in the water that has risen around them and forced their inhabitants out — until we arrive at a house with twin lime green gabled roofs, matching green curtains blowing in open windows and steps of cream-colored tile that descend right into the water. Several geteks are tied to a dock floating in what would have been the front yard. On another floating dock beside the house, two women in headscarves and straw hats clean and sort fish.

Inside, Mister Robbani introduces me to the inhabitants. When I ask the name of the place, they are momentarily lost for words. “Klapatuju,” Mister Robbani says finally. “It was called Klapatuju. One hundred families lived here. Few are left.”

Where once there was a village with a name

and a history, now there is a watery plain and a memory of a place that was.

How could this happen? I ask. They walk me to the window and point to a low dark line of forest in the far distance. “That is where the peat forest is,” Mister Robbani says. “The company drains the land there, and the water comes here.”

*

After a brief talk, we descend to the boat to make another visit, this time to the home of a short, angular man named Sarip who lives by fishing with his wife and two small sons. Mister Sarip’s house is far less elegant than the last — weathered boards under a rusted tin roof. The family’s possessions are tied by thin cords to the rafters: a vinyl backpack embossed with Dora the Explorer, a faded pink teddy bear the size of a small child, still wrapped in plastic.

Some months ago, Sarip tells me, the house — even now just inches above the flood — was inundated with water for weeks. He built a platform with pontoons of bamboo on which the family would sleep, afloat on a raft inside their home. They know the flood could, and likely will, rise again at any moment. “We can’t leave because we have nowhere to go,” Mister Sarip says, his two sons clinging to his legs. “I am sad for losing what we had once, but I am most sad for my children. We have no money for school fees, and anyway we need the children to catch fish to sell in the village. I worry for their future.”

Everyone worries about the future — but in the case of Mister Sarip and his children living on nothing but fish in a landscape of rising water, the understatement is overwhelming.

*

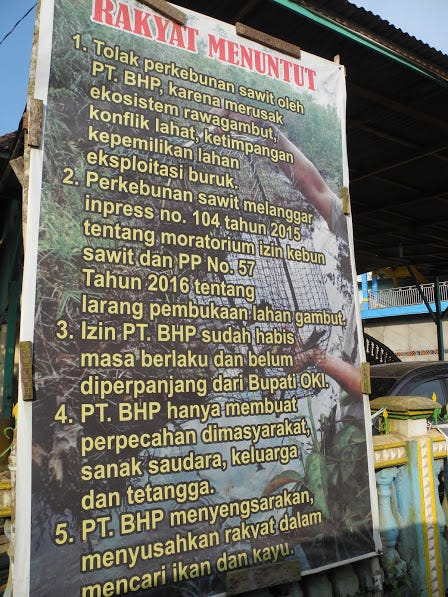

A few miles upriver in the village of Lebung Itam, the farmers are gathered to tell me their stories. Here another company, called Bintang Harapan Palma, is negotiating with the district government for 25,000 acres of peatland to drain and plant oil palm. But the villagers have seen what this leads to, and they don’t want it.

“We can’t leave because we have nowhere to go”

The villagers quickly usher me inside a house and file in with excitement. Muhammed Sayafei, a white-haired man in a long white kaftan and a kufi cap, shakes my hand warmly and invites me to sit with him on an upholstered sofa as 20 or so others squat or sit cross-legged facing us.

“We are sufficient here,” he says in quick, confident English. “We can earn enough money and we can stand on our own foot. So we tell the company to go away. We hope you will help us fight the company. We will not let them take our land.”

Mister Sayafei knows I am here to support, so I play devil’s advocate. “Don’t you want the income the company will bring?” I ask him. He abruptly waves his finger in the air and shouts, “No! Income of people will decrease. Water level will push us away. We will have trauma from conflict with the company.”

He looks around at the room full of his neighbors, most of whom don’t understand a word we’re saying. “We don’t like capitalism!” he exclaims.

I smile and nod, but continue gently prodding. “Why doesn’t your government help?” I ask. Mister Sayafei rubs his fingers and thumb together in a universal gesture and says, “Too simple! It’s about the money.”

The next day at sunrise, as the morning swathes the village houses in jungle mist, we descend to a narrow canal where three brightly painted geteks await. The water is black as India ink — “root water” they call it, because a dye from the roots of melaleuca trees paints the water black.

We climb into the geteks and motor out of the village into the peatlands. The canal cuts deep into the land, the banks thick with ferns and reeds rising as much as two meters above us, showing the depth of the peat. Peat is vegetable soil, layer upon layer of leaf-fall and downed trees piled up for thousands of years, dense with carbon and rich with life. The villagers tell me the peat here is 10 meters deep in some places.

After maybe 30 minutes, we arrive at the canal’s end, where several villagers are taking a rest from their work on a thatch-roofed platform set on narrow stilts. Using few words, a man named Faharul, with a thin mustache, a jaunty fedora and an easy smile, demonstrates their work. They are digging the canal 10 meters a week, pulling out peat and piling it on the banks with their bare hands (“hands better than tools,” he says).

With a long metal rod they root into the deep peat until they detect buried timber. Using nothing but muscle and grit, they pull up trees that may have been downed a century ago or more. The prize is meranti — the tallest and toughest wood here — and with a chainsaw they mill the deep red wood into boards and float it back to the village where they build with it or sell it.

Cured for decades under the peat, the wood is tough as steel and makes the best houses, they tell me.

“This is how our parents built our houses,” Faharul says. “And this is how we will build our children’s houses. Nothing in nature is harmed by our activity. We leave the peat intact. The forest can take care of itself, until someone comes to take it. This is why we want to protect our peatlands from the plantation companies.”

*

Flood and fire, fire and flood: the two faces of the climate crisis. Like the massive fires that tore through Indonesia’s drained and dried peatlands in 2015 sending tens of thousands to hospitals and emergency shelters, the flooding that reshapes villages along Sumatra’s Musi River is a man-made disaster — and a crime. That the motive for these crimes is the production of a cheap commodity oil used in snack chips, lipstick and “renewable” biofuels is an abomination.

“The forest can take care of itself, until someone comes to take it.”

Indonesia’s vast peat marshes are the most dense carbon stores on earth — to the extent that draining and drying them is on par with burning fossil fuels as a leading cause of greenhouse gas emissions. The elemental forces that doomed the village of Klapatuju are not elemental at all. They are the same forces that, on a larger scale, doom the islands of Vanuatu in the Pacific and Isle de Jean Charles in the Gulf of Mexico, that sent Hurricane Sandy tearing through New York and Katrina through New Orleans and that will, sooner rather than later, take Miami and Houston. You and I are not so different from Mister Sarip and his floating sleeping platform and his children whose future is a vast watery plain. We can’t leave because we have nowhere else to go.

But we can instead choose to join the fight of Muhammed Sayafei and Faharul and the villagers of Lebung Itam. We can heed the warnings of what we’ve done to the earth’s ecosystems and have the foresight and the courage to claw another path — one that, to the greatest degree possible, makes peace with the elements and allows the land and the water some hope of recovery.