Plant-forward food: A powerful step toward climate-friendly schools

by Kari Hamerschalg, deputy director of food and agriculture, and Julian Kraus-Polk, consultant for Friends of the Earth

Originally posted in Green Schools Catalyst Quarterly

In an effort to take on the climate crisis, schools across the nation are installing solar panels and energy-efficient lighting, planting trees, and implementing recycling programs. This is a great start! However, to make an even greater impact, schools must turn their attention to one of the most powerful and cost-effective ways to slash their greenhouse gas emissions: changing school lunch.

School lunch may seem like a small player in combatting our massive climate challenges. Yet, with up to seven billion school meals served annually, small menu shifts that swap meat dishes for plant-based entrees can significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions and other environmental harms. Serving less processed meat and more plant-based foods is also in greater alignment with the U.S. Dietary Guidelines and numerous public health organizations’ recommendations (Bouvard et al., 2015; Hamerschlag, Dalton, and Kraus-Polk, 2018).

Friends of the Earth estimates that if every U.S. public school swapped out a beef burger for a veggie burger just twice a month, we would save 2.8 billion pounds of CO2eq — the equivalent of not burning 144 million gallons of gas or 1.4 billion pounds of coal (Hamerschlag, Dalton, and Kraus-Polk, 2018).

Schools can also contribute to climate resiliency and reduced pesticide use by sourcing more organic foods from local and regional producers, while moving away from a food service model dominated by cheap, highly processed, meat-centric meals. With ecological catastrophe looming, all schools can act now to make these powerful, cost-effective shifts in their cafeterias. These changes will help mitigate climate change, enhance student health, and promote a generational shift in consumption habits that could save lives and billions in health care costs. Two recent reports by Friends of the Earth highlight this growing movement.

With more than 1.7 million members and activists across all 50 states, Friends of the Earth fights to protect our environment and create a healthy and just world. Its food and agriculture program works to rapidly transition the food system to one that is regenerative, healthy, and just. Recognizing the major health and climate impacts of high meat consumption in the U.S., the organization’s climate-friendly food service initiative aims to shift K-12, university, state, and municipal purchasing toward more climate-friendly, plant-based foods and smaller portions of regionally sourced, organic, and pasture-raised animal-based foods.

How does Friends of the Earth define climate-friendly and plant-forward school food?

- Foods with low carbon and water footprints. Plant-based foods are 100% sourced from plants (e.g., beans, lentils, soy products, whole grains, nuts, and seeds). Plant-forward foods swap out some of the meat for plant-based foods, resulting in plant-strong, lower-meat recipes (e.g., bean and turkey chili, mushroom-beef burgers).

- Foods produced using organic farming practices that reduce greenhouse gases (e.g., no synthetic fertilizers) and sequester carbon in the soil (e.g., cover cropping). Ideally, these foods are sourced from local and regional, small- and mid-scale, diversified farms (e.g., farm to school programs).

- Minimally packaged foods and implementation of food waste reduction strategies (e.g., serving sliced fruit, longer lunch periods, lunch after recess, nutrition education including food waste information, and “share tables” that allow students to share untouched food).

The Reports

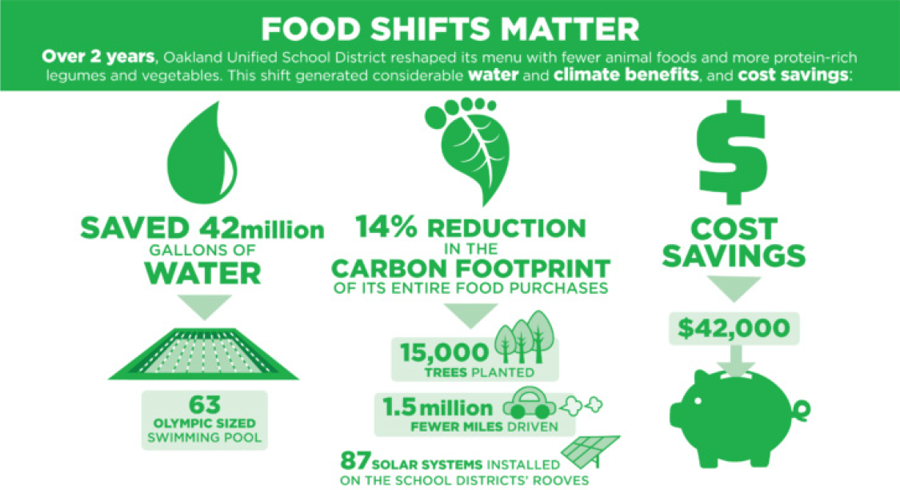

In 2017, Friends of the Earth published a case study of Oakland Unified School District that demonstrated how shifting to plant-forward food produced significant environmental and financial benefits while increasing student meal satisfaction and serving more local, organic, and sustainable meat (Hamerschlag and Kraus-Polk, 2017) (see Figure 1).

The Oakland case study is compelling, but even more remarkable is the broader trend of school districts nationwide that are implementing similar strategies and moving toward healthy, climate-friendly school food. In 2018, Friends of the Earth published Scaling Up Healthy, Climate-Friendly School Food (Hamerschlag, Dalton, and Kraus-Polk, 2018), a report that documents key strategies from 18 school districts across the country that have been pioneering plant-forward menus within distinct cultural contexts and varied food service capacities.

This article draws on that 2018 report to highlight benefits and effective strategies for increasing access to healthy, climate-friendly school food.

Why Plant-Forward? Dual Benefits – Environmental and Health

To the age-old question — “what should humans eat for good health?” — best-selling author Michael Pollan offered a simple, yet compelling answer: “Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants” (Pollan, 2007). It turns out, this is also a powerful answer to the question, “what should humans eat to mitigate climate change and protect our environment?”

The agricultural sector represents a quarter of global greenhouse gas emissions, the majority of which come from livestock production (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2017). Global livestock production alone represents 14.5% of all anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, more than the entire transportation sector (United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, 2019). Yet, limiting emissions by reducing food animal consumption is often ignored as a key solution to the crisis. The United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change found that reducing consumption of animal products is one of the highest impact actions for mitigating food and agriculture emissions (Smith et al., 2014). Project Drawdown’s team of experts and scientists similarly identified food waste reduction and shifting to a plant-rich diet as two of the most powerful solutions to reverse climate change (Project Drawdown, n.d.). Numerous studies have also shown that even if other sectors drastically reduce emissions, we cannot effectively mitigate climate change without dramatically reducing consumption of industrial animal products (GRAIN and the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy, 2018).

There is broad public health consensus that eating more plants and less meat is also better for our health (Hamerschlag, Dalton, and Kraus-Polk, 2018). The U.S. Dietary Guidelines assert that teenage boys and men are eating too much meat and children on average are not eating enough vegetables, legumes, nuts, seeds, and other plant-based foods (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2015). Evidence shows that eating less meat, especially processed meat, and more plant-based foods can decrease risks of costly and deadly diseases such as heart disease, diabetes, obesity, and some cancers. Small diet shifts can also potentially save our nation billions of dollars in costs from diet-related chronic diseases (Springmann et al., 2016).

School Food’s Problematic Status Quo

Overcoming School Food Stigma

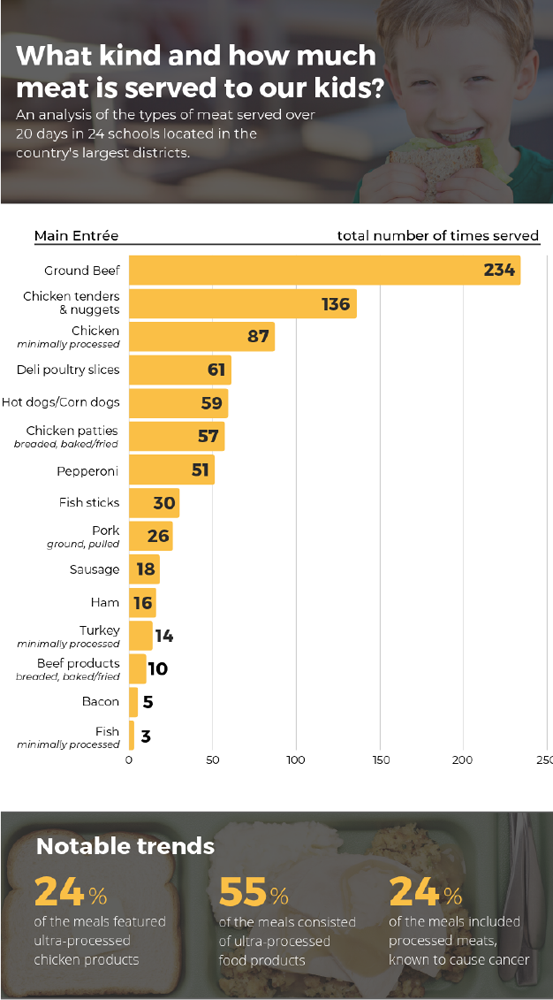

The tremendous growth in farm to school and garden programs has greatly expanded access to fresh fruits and vegetables and, to a lesser extent, more sustainable meat. Despite progress, school food remains largely grounded in a corporate-controlled fast food paradigm — cheap, pre-packaged, meat-centric, and highly processed (see Figure 2). In the 1980s when the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) National School Lunch Program experienced major funding cuts, there was a precipitous slide toward more privatized food service and diminished food quality (Rude, 2016). School food started to look more and more like fast food. Many schools now lack adequate cooking facilities and rely on heat-and-serve equipment to prepare premade, excessively packaged meals with highly processed ingredients. A number of school food professionals who were interviewed for the 2018 Scaling Up report noted that the over reliance on heat-and-serve, highly processed food has led to a stigma around school food (Hamerschlag, Dalton, and Kraus-Polk, 2018). In turn, this reduces participation of those who can pay full price, leading to greater financial constraints and the serving of more processed, lower quality food. Most students eating school food are low-income and disproportionately students of color, who are already at risk for diabetes and obesity (Conway et al., 2018; Sekhar, 2010). In other words, the prevalence of unhealthy, highly processed food in schools is also fundamentally an issue of equity. In 2018, 74% of public school meals served in the U.S. were free or reduced-price. The majority of students receiving free or reduced-price meals were below 130% of the poverty line (School Nutrition Association, 2018). According to the USDA, the number of students who received free meals was more than double the rate of those who paid full price (78% versus 35%) (U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service, 2019).

Big Food has dictated that ‘kid’ food’ is bite-sized and pre-packaged. Which is why many just assume that kids only like fried chicken nuggets, pepperoni, and hotdogs—all highly processed meat products that are known to be bad for our health and even worse for the climate.” – Bertrand Weber, Minneapolis Public Schools (Hamerschlag, Dalton, and Kraus-Polk, 2018, p. 19).

Processed Foods and Factory-Farmed Meats Dominate Menus

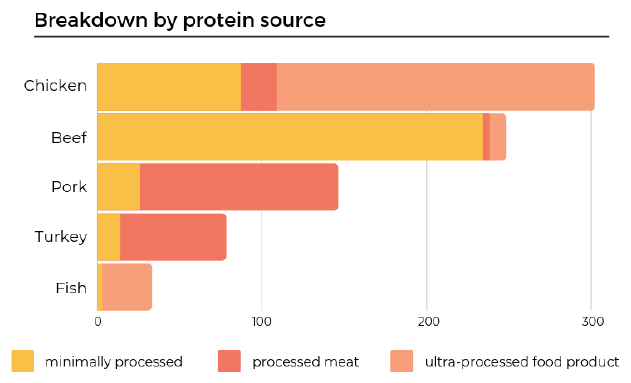

Despite many improvements since the passage of the 2010 Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act, the majority of K-12 school meals are still out of alignment with healthy, climate-friendly eating patterns. According to Balanced’s analysis of 24 of the nation’s largest school districts, 55% of meals consisted of ultra-processed food products, while 24% of meals included processed meats that are known to increase cancer risks (Balanced, 2019).

“Processed meats” are salted, cured, or treated with nitrates or nitrites (i.e., hot dogs, sausages, pepperoni, lunch meats, etc.). Chicken nuggets, which are considered an “ultra-processed food product,” have been linked to cancer, though with a lesser degree of certainty than processed meats (Meredith, 2018).

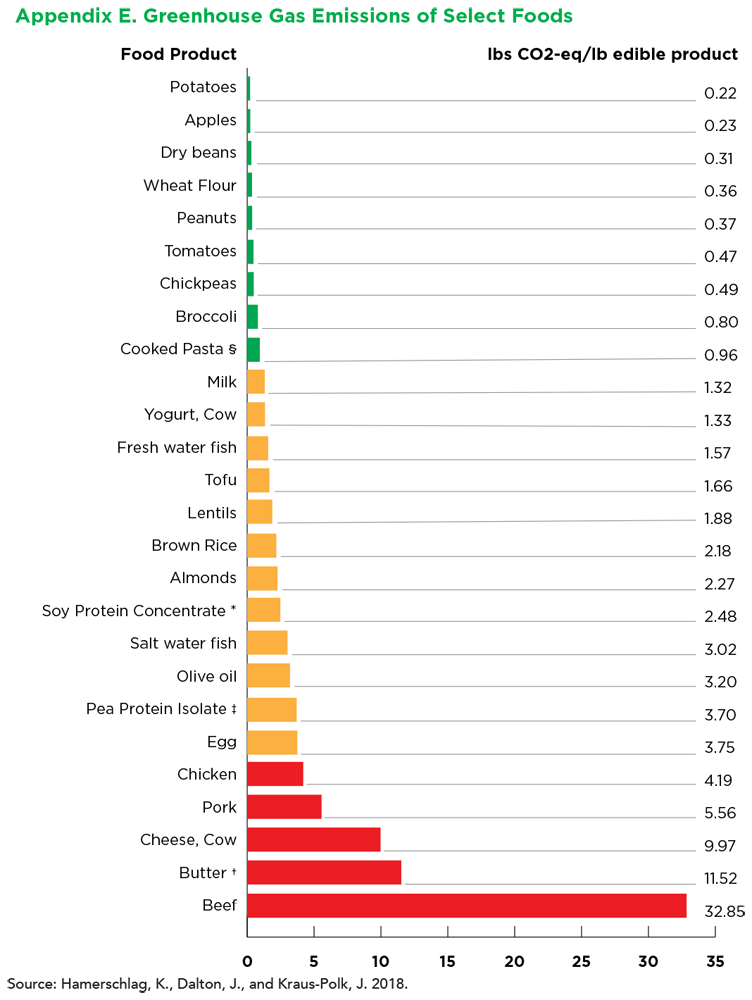

Chicken is the most popular meat served in schools—mostly in ultra-processed form—while ground beef is the second most common. Beef is also the most carbon intensive meat (Heller et al., 2018). (See chart on the next page, Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Select Foods, to see how greenhouse gas emissions compare by food type.) Pound for pound, beef is 25 to 34 times more carbon-intensive than legumes such as beans and lentils (Heller et al., 2018). Unfortunately, most schools do not regularly serve these legumes and other healthy, low-carbon foods. Friends of the Earth’s 2018 Scaling Up report found that most major school districts do not offer hot plant-based entrees and those that do tend to offer less healthy items like cheese pizza (Hamerschlag, Dalton, Kraus-Polk, 2018).

Government Subsidies and Policies Inhibit Healthy, Climate-Friendly Food

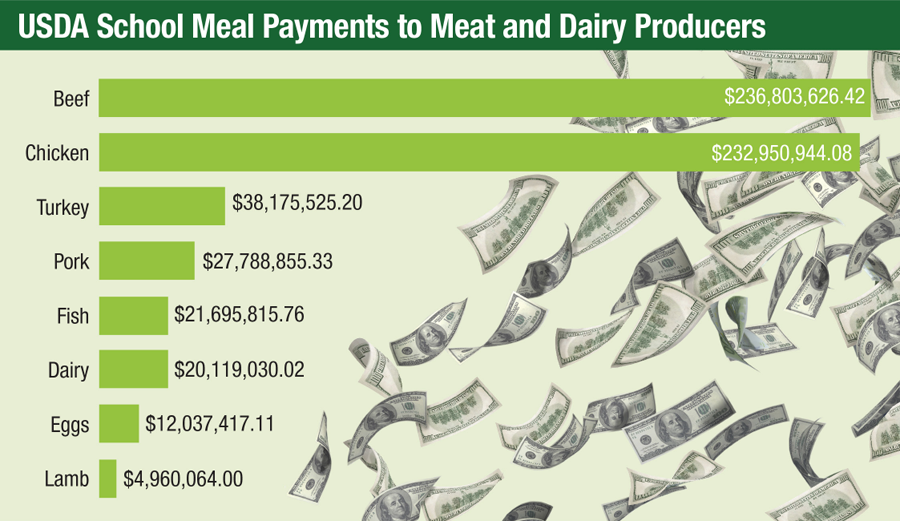

Billions of dollars in government subsidiesand programs––geared toward supporting the production and marketing of industrial animal products––are a major obstacle, stifling wider adoption of healthy, climate-friendly food. A 2015 Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine report that focused on subsidies found that “in 2013, the U.S. Department of Agriculture paid more than $500 million to 62 meat and dairy producers for beef, chicken, turkey, pork, fish, dairy, eggs, and lamb that ended up in school meals” through the Schools/Child Nutrition USDA Foods Program (Barnard, 2016) (Figure 3). Healthy and more climate-friendly fruits, vegetables, and legumes received just a tiny fraction of that money.

In addition, regulations that require schools to offer cow’s milk to receive full reimbursement promote waste and unnecessary consumption of milk products. The rule is also unjust “given the high rates of lactose intolerance among students of color, who make up the majority of students who receive free and reduced-price school meals” (Hamerschlag, Dalton, and Kraus-Polk, 2018). Friends of the Earth’s 2018 Scaling Up report highlighted other problematic school food policies, including the failure to allow plant-based proteins like seitan and quinoa to receive credit as protein; the need to serve unnecessarily large portions of plant-based foods for them to receive credit as protein; and the generally low reimbursement rates for school meals. Increasing the reimbursement is needed to cover rising labor costs and enable cooking of higher quality, whole, plant-based foods.

Successful Strategies for Boosting Participation and Serving Climate-Friendly Food

Serving more plant-based food is a relatively simple solution to complex environmental and health challenges. Yet, overcoming structural barriers and ensuring greater acceptance by kids, parents, and cafeteria staff requires political will and a concerted set of integrated strategies, adapted to each district’s cultural context. Since participation rates impact food service budgets, school food needs to be more appealing––both to kids who qualify for free and reduced-price meals and to those who can pay full price. The following strategies have been tested and proven successful for boosting participation rates and getting more students on board with healthy, plant-based food. While the leadership and vision of food service directors and staff is pivotal to making these changes, it is also vital to have engaged support from school leaders, teachers, students, parents, and school board members.

Serving Plant-Forward Menus in a Friendly Dining Environment

By curating a friendly and fun food environment that emulates popular trends in dining, many school districts have cited the following strategies as helpful for increasing participation rates while shifting to more plant-forward meals (Hamerschlag, Dalton, and Kraus-Polk, 2018).

- Salad bars with plant-based proteins: Many schools use salad bars as a way to offer students a plant-based meal every day, featuring variety and choice.

- Food trucks: Colorado’s Boulder Valley School District, Texas’ Austin Independent School District, and California’s Santa Barbara Unified School District feature food trucks as a lunchtime option. This hip, convenient dining style attracts wider school food participation—and more business means more resources for quality ingredients and innovative plant-based options.

- Food courts: In 2019, Florida’s Lee County Schools will pilot a 100% plant-based line in food courts across the district. California’s Riverside Unified School District sports large banners that highlight globally-themed cuisines.

- Build-a-bowl stations: Minnesota’s Minneapolis Public Schools, Texas’ Dallas Independent School District, Lee County Schools, and California’s San Luis Coastal Unified School District and Riverside Unified School District serve trendy protein bowls, often featuring locally sourced and plant-based ingredients.

- Grab-and-go carts: Missouri’s St. Louis Public Schools and California’s Ukiah Unified School District are increasing acceptance of plant-based options by making them convenient.

- Plant-based pop-up “restaurants”: Riverside Unified School District implements pop-ups to draw attention to and familiarize students with new plant-based menu items.

- Ready-to-eat veggie protein packs: In 2019, St. Louis Public Schools will roll out ready-to-eat packs with fruits and vegetables, sun butters, and other plant proteins, like hummus.

Promoting Plant-Forward Food through Student Engagement

Although plant-forward eating is on the rise, strong cultural preferences for meat-based foods persist, along with misguided perceptions that plant-based meals do not contain sufficient protein (McDougall, 2002). Moreover, students who rely on school lunch as their main meal are less inclined to select a new and unfamiliar plant-based item. To overcome these challenges, school districts have adopted the following innovative student engagement, education, and marketing strategies.

- Taste tests and “Try it” days: These strategies are the most common ways in which school districts encourage kids to try new plant-based foods before they go on the menu. St. Louis Public Schools has a “Try it Tuesday” program to introduce students to new foods.

- Student advisory councils: California’s San Francisco and San Diego Unified School Districts have created student committees to taste new recipes, make suggestions, and assist in recipe development and promotion.

- Marketing strategies that emphasize flavor over health are most effective: Labeling items “vegan” or “vegetarian” can be counter-productive, making it appear as if these items are for vegans or vegetarians only. Meatless Mondays and Green Mondays offer great marketing opportunities and ready-to-use materials.

- Recipe competitions featuring vegetarian and plant-based categories: Boulder Valley School District, San Diego Unified School District, and North Carolina’s Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools engage students in celebrity chef-style recipe contests. Winning recipes are featured on school menus.

- Nutrition education: Many organizations, including Wellness in the Schools, Lean and Green Kids, The Edible Schoolyard Project, FoodCorps, Center for Ecoliteracy, and the Coalition for Healthy School Food offer farm to school, garden, cooking, and plant-forward nutrition educational activities that inspire students to try healthy, new foods.

- Parent-focused education: Communicating with parents about school food shifts—through parent-teacher associations, wellness and sustainability committees, special presentations, or other means—is critical to help them appreciate and support the values behind healthier plant-forward options.

Investing in Higher Quality Fresh Food, Trained Staff, and Kitchen Equipment

To gain student support, climate-friendly, plant-forward meals must be delicious—and “delicious food requires good ingredients, good cooks, good equipment and good recipes” (Hamerschlag, Dalton, and Kraus-Polk, 2018). School districts that have had the most success with climate-friendly food tend to cook meals from scratch with fresh produce from local farms. The following effective strategies are used to transition to more climate-friendly menus.

- Training school cooks to prepare plant-forward recipes is essential, as is providing information to help cafeteria staff become climate-friendly food ambassadors. Forward Food offers free staff training.

- Investing in scratch cooking facilities allows for greater use of fresh, local, climate-friendly food. While large capital investments and more labor are required, scratch cooking is deemed a healthier, more just, and cost-effective approach in the long run.

- Procuring fresh, locally sourced food connects students to their food, which boosts satisfaction and participation.

- Using speed scratch cooking and premade products. Schools without full kitchens can use premade products or simple and fresher speed scratch recipes. Speed scratch indicates using a combination of premade products (e.g., canned beans, frozen burrito) and fresh ingredients (e.g., avocado, chopped tomatoes). (Here is a product list of premade veggie items.)

- Identifying popular recipes. Climate-friendly food includes plant-based and plant-forward foods such as blended burgers, reduced-meat tacos, and chilis that blend meat (ideally sustainable) with legumes.

- Adopting cost-effective procurement practices. Scratch-cooked plant-based and plant-forward meals can be considerably cheaper than meat-forward entrees, and low-cost USDA commodity beans can make plant-forward entrees more affordable.

Policy is Powerful

To make healthy, climate-friendly food the norm for students across the country, policy change—supported by a wide range of school stakeholders—is needed at district, state, and federal levels. Friends of the Earth’s 2018 Scaling Up report outlines policy proposals in each of these arenas. In the past several years, we have seen important progress at school district and state levels, including:

- In December 2018, Washington, D.C.’s city council approved the Healthy Students Amendment Act that makes D.C. the first local government to require that vegetarian options be proactively provided to students at breakfast and lunch.

- In May 2019, the California Assembly approved Assembly Bill 479 to provide grant funding and reimbursements to public schools for the costs of expanding plant-based food and beverages. The bill, subsequently approved by the California Senate Education Committee, will continue to be under consideration in 2020.

- Eight school districts have adopted the Good Food Purchasing Program—a comprehensive, values-based policy initiative that encourages healthier foods, increased local sourcing, and higher animal welfare and environmental standards, including more climate-friendly, plant-based, or organic options in school meals.

- Measure 20-227 in Eugene, Oregon; Measure H in Napa, California; Measure J in Oakland, California; Measure T in Lakeport, California; and the City School Bond Measure in St. Louis, Missouri, among others, provide a model for community-based revenue generation to fund kitchen improvements.

Role of Community: It Takes A Village

While food service leadership and staff play the biggest role in shifting school food menus, the role of the broader community is key in engaging students and ensuring that the food service department has the necessary resources, support, and encouragement to overcome real obstacles.

- School board members and administrators can support bigger investments in labor, kitchen facilities, and dining environments. They can also make sure students have enough time to eat; promote and invest district resources in food education (e.g., school gardens, culinary arts, educational curricula); and recruit and hire innovative and passionate food service directors.

- Teachers can be positive role models by eating with kids and encouraging them to try plant-based foods. They can also integrate food education into their curricula and bring food education organizations into the classroom.

- Parents can volunteer at lunchtime. They can help with taste tests or new cafeteria initiatives. They can build support among parents for climate-friendly food by organizing educational events. They can also offer political support and/or encouragement to school food service staff who may or may not want to implement these changes.

- Nonprofit partners can provide technical and other support, often free of charge, to help school districts transition toward more plant-forward menus—including Friends of the Earth, Forward Food, The Chef Ann Foundation, Center for Ecoliteracy, Good Food Purchasing Program, Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine, Meatless Mondays, One Meal a Day for the Planet, Wellness in the Schools, Lean and Green Kids, and the Coalition for Healthy School Food.

Ultimately, the broad community of healthy school food stakeholders must come together to support state and federal policy reforms that make it more viable to serve healthier, fresh, plant-forward and organic food, in conjunction with nutrition education programming. Significant community mobilization is also needed to pass local ballot initiatives and infrastructure bonds that invest in better kitchen facilities and dining environments.

Conclusion

Transforming school food should be an urgent national priority. By reducing demand for resource-intensive animal foods, schools can greatly reduce the vast greenhouse gas emissions associated with the seven billion school meals served annually. These cost-effective menu shifts, which will also deliver significant health benefits, will be much more successful when combined with food, nutrition, sustainability, climate, and garden education programs. The strategies outlined above to promote plant-based and plant-forward food also support important parallel efforts to expand fresh, locally sourced, organic, scratch-cooked meals—all interrelated elements of the broader healthy, sustainable school food movement. We hope that more stakeholders from the school sustainability community will join the growing movement toward healthy, climate-friendly food. The future of our children’s health, and the planet itself, requires this broad coalition effort.

Works Cited

Balanced. (n.d). Healthy menus, healthy children. Balanced.org. Retrieved from: https://www.balanced.org/schools

Barnard, N. (2016). Meat and dairy subsidies make America sick. Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine. Retrieved from: https://www.pcrm.org/news/blog/meat-and-dairy-subsidies-make-america-sick

Bouvard, V., Loomis, D., Guyton, K., Grosse, Y., Ghissassi, F., Benbrahim-Tallaa, L., Guha, N., Mattock, H., Straif, K., and International Agency for Research on Cancer Monograph Working Group. (2015). Carcinogenicity of consumption of red and processed meat. Lancet Oncology, 16(16), p. 1599. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00444-1

Conway, B., Han, X., Munro, H., Gross, A., Shu, X., Hargreaves, M., Zheng, W., Powers, A., and Blot, W. (2018). The obesity epidemic and rising diabetes incidence in a low-income racially diverse southern US cohort. PLoS One, 13(1): e0190993. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0190993

GRAIN and the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy. (2018). Emissions impossible: How big meat and dairy are heating up the planet. GRAIN. Retrieved from https://www.grain.org/article/entries/5976-emissions-impossible-how-big-meat-and-dairy-are-heating-up-the-planet

Hamerschlag, K., Dalton, J., and Kraus-Polk, J. (2018). Scaling up healthy, climate-friendly school food. Friends of the Earth. Retrieved from: https://foe.org/resources/scaling-healthy-climate-friendly-school-food/

Hamerschlag, K. and Kraus-Polk, J. (2017). Shrinking the carbon and water footprint of school food: A recipe for combating climate change. A pilot analysis of Oakland Unified School District’s food programs. Friends of the Earth. Retrieved from: https://foe.org/resources/shrinking-carbon-water-footprint-school-food/

Heller, M., Willits-Smith, A., Meyer, R., Keoleian G., and Rose, D. (2018). Greenhouse gas emissions and energy use associated with production of individual self-selected US diets. Environmental Research Letters, 13(4). Retrieved from: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/aab0ac

McDougall, J. (2002). Plant foods have a complete amino acid composition. Circulation, 105(25). https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.0000018905.97677.1F

Meredith, S. (2018). Eating ultra-processed foods like chicken nuggets ‘linked to cancer,’ study says. CNBC. Retrieved from: https://www.cnbc.com/2018/02/15/study-ultra-processed-foods-like-chicken-nuggets-linked-to-cancer.html

Pollan, M. (2007). Unhappy meals. The New York Times Magazine. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2007/01/28/magazine/28nutritionism.t.html

Project Drawdown. (n.d.). Solutions by rank. Retrieved from: https://www.drawdown.org/solutions

Rude, E. (2016). An abbreviated history of school lunch in America. Time Magazine. Retrieved from: https://time.com/4496771/school-lunch-history/

School Nutrition Association. (2018). School meal trends and stats. Retrieved from: https://schoolnutrition.org/aboutschoolmeals/schoolmealtrendsstats/

Sekhar, S. (2010). The significance of childhood obesity in communities of color. Center for American Progress. Retrieved from: https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/healthcare/reports/2010/06/14/7908/the-significance-of-childhood-obesity-in-communities-of-color/

Smith, P., Bustamante, M., Ahammad H., Clark, H., Dong, H., Elsiddig, E., Haberl, H., Harper, R., House, J., Jafari, M., Masera, O., Mbow, C., Ravindranath, N., Rice, C., Robledo Abad, C., Romanovskaya, A., Sperling, F., and Tubiello, F. (2014). Agriculture, forestry and other land use (AFOLU). In: Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Edenhofer, O., Pichs-Madruga, R., Sokona, Y., Farahani, E., Kadner, S., Seyboth, K., Adler, A., Baum, I., Brunner, S., Eickemeier, P., Kriemann, B., Savolainen, J., Schlömer, S., von Stechow, C., Zwickel, T., and Minx, J. (eds.)]. Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/02/ipcc_wg3_ar5_chapter11.pdf

Springmann, M., Godfray, C., Rayner, M., and Scarborough, P. (2016). Analysis and valuation of the health and climate change cobenefits of dietary change. PNAS, 113(15), 4146 – 4151. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1523119113

United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. (2019). Key facts and findings. Retrieved from: http://www.fao.org/news/story/en/item/197623/icode/

U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service. (2019). School nutrition and meal cost study: Summary of findings. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Retrieved from: https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/resource-files/SNMCS_Summary-Findings.pdf

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2015). 2015 – 2020 Dietary guidelines for Americans 2015 – 2020. 8th Edition. Retrieved from: https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/resources/2015-2020_Dietary_Guidelines.pdf U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2017). Greenhouse gas emissions. Retrieved from: https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/global-greenhouse-gas-emissions-data

Related Posts

Ways to Support Our Work

Read Latest News

Stay informed and inspired. Read our latest press releases to see how we’re making a difference for the planet.

See Our Impact

See the real wins your support made possible. Read about the campaign wins we’ve fought for and won together.

Donate Today

Help power change. It takes support from environmental champions like you to build a more healthy and just world.