- Blog

- Forests

- Land Grabbing, Forests & Finance

- Today is Indigenous Peoples Day. Where is the finance sector?

Today is Indigenous Peoples Day. Where is the finance sector?

by Jeff Conant, senior international forest program manager

Donate Now!

Your contribution will benefit Friends of the Earth.

Stay Informed

Thanks for your interest in Friends of the Earth. You can find information about us and get in touch the following ways:

“One does not sell the land people walk on.”

— Crazy Horse, Oglala Lakota warrior chief

At the very beginning of 2020, BlackRock, the world’s largest money manager, announced it would place the climate crisis at the center of its investment strategy, stating that “climate risk is investment risk.” The decision included a divestment from coal, greater engagement with polluting companies, and placing sustainability at the core of its business – but it notably lacked an explicit commitment to address investments in extreme dirty energy projects like the Alberta tar sands or oil extraction in the Arctic. It also said nothing about deforestation, the second leading driver of climate chaos. And, like virtually every other commitment to green financing that we’re seeing from the finance sector, BlackRock’s big (and as yet, unfulfilled) promise made no mention of the human rights of Indigenous and tribal peoples and local communities who face the frontline impacts of the industries driving the climate crisis.

Let’s be clear: all exploitation of resources by our industrial society depends on exploitation of the people within whose lands and territories those resources lie. When it comes to a just transition to a clean and green economy, protection of Indigenous peoples’ rights needs to be at the top of the discussion, and Indigenous peoples’ organizations need to be at the table.

Deforestation and forest degradation – largely driven by the industrial production of agricultural commodities like palm oil, cattle, soy, pulp and paper, and biomass feedstock – is the second largest contributor to the climate crisis after fossil fuels. These industries are also routinely involved in gross human rights abuses, land grabbing, and destruction of critical wildlife habitat. A 2019 study found that three land and environmental defenders were killed every week and agribusiness was the second deadliest sector, after mining and extractives. Of those land defenders killed worldwide, almost 40 percent are indigenous.

It’s now well-established that the best way to protect the world’s tropical forests is to recognize and respect the legal and customary rights and self-determination of Indigenous and tribal peoples and local communities who live in and care for forests. This requires, at minimum, direct consultation on operations that affect Indigenous Peoples, accountability for rights violations, and compliance with the internationally recognized right to Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC), which was first enshrined in international law as a centerpiece of the hard-won UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples over a decade ago.

Yet not a single global investment firm or money manager has an explicit policy or set of guidelines to recognize the right to Free Prior and Informed Consent, let alone to address the fundamental rights of indigenous peoples more broadly.

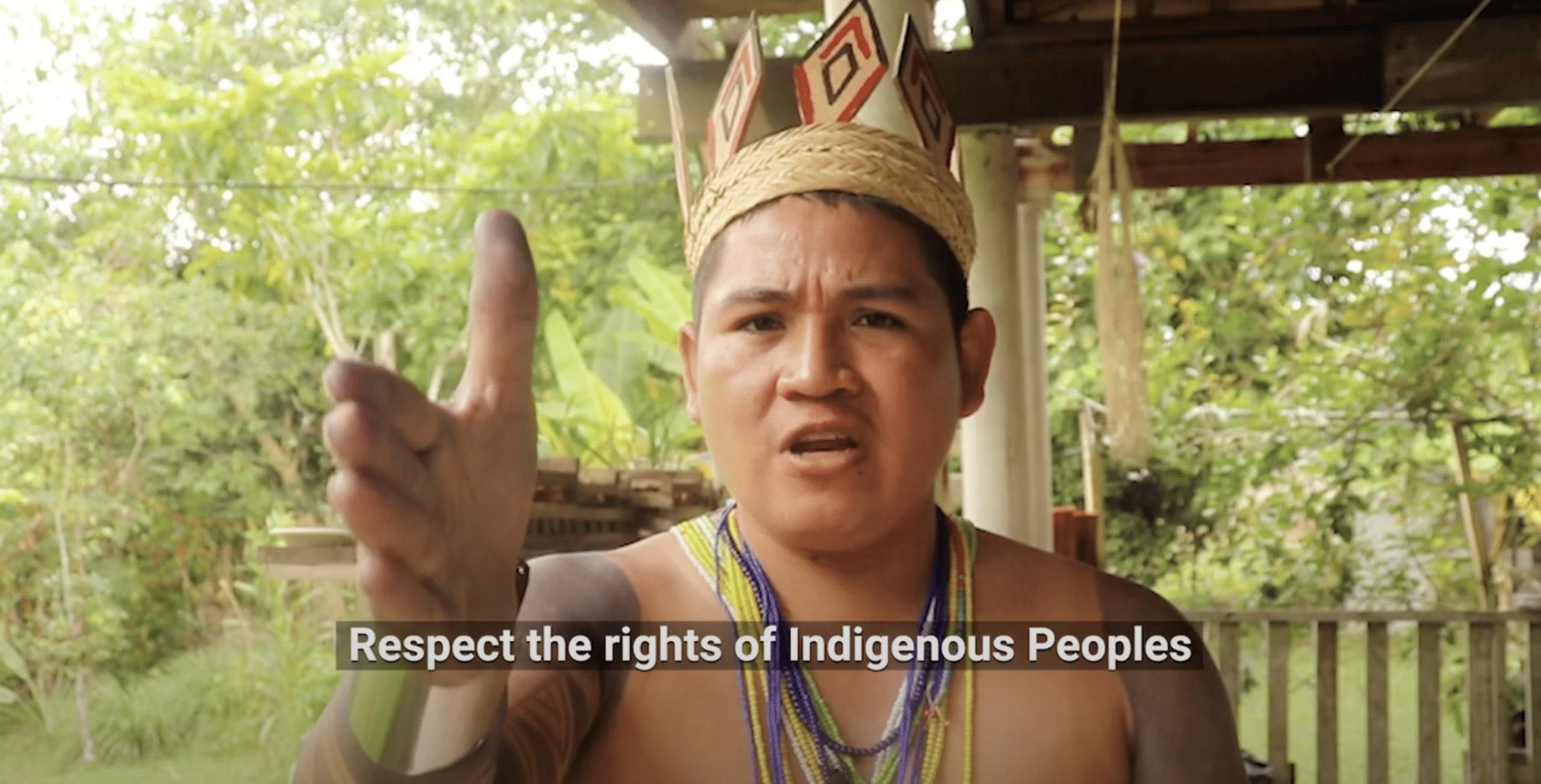

That’s why indigenous peoples worldwide are increasingly raising their voices to demand that the finance sector step up.

Indigenous Peoples’ rights, land rights, and forest destruction are first and foremost ethical, moral and human issues. But they are also investment issues. The UN Environment Programme says that “Banks and investors can drive deforestation and land conversion through their lending and investment practices,” and even the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development – a collection of the world’s largest economic powers – says in its guidelines that financial companies are “directly linked” to the social and environmental impacts of their investments and bear responsibility for resolving them. The UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights provide a framework for private companies, including financial firms, to safeguard human rights. This is expressed through three pillars: the state has a duty to protect against human rights abuses, businesses have a responsibility to respect human rights, and victims of human rights abuses have the right to effective remedy.

In other words, international human rights law makes it abundantly clear that money managers are directly responsible for driving the global assault on Indigenous Peoples and their lands and territories and must be held accountable.

It’s to that end that Friends of the Earth, Amazon Watch and other partners have put together this set of Principles for Asset Managers on forests and human rights, which we’ll be advancing in our campaigns in the coming months and years. We’ve included these principles in our recommendations to the Big Three money managers published last month, we’ve sent them to dozens of state pension funds, and we’re working with responsible asset owners like New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer to create a foundation of understanding in the finance world that human rights and social justice are fundamental to climate-positive investing. We’ve also joined the Zero Tolerance Initiative to push global businesses to deter violence of any sort against environmental human rights defenders.

Pressuring financial institutions to change their investment practices and adhere to international covenants is still a far cry from the type of profound reparations needed to heal the deep wounds of history or restore justice to the peoples at whose expense our entire industrial civilization is built. But it is an important and necessary step in the right direction.