- Blog

- Sustainable Economic Systems

- International Sustainable Finance

- Villagers suffer at the hands of Mozambique’s LNG gas development

Villagers suffer at the hands of Mozambique’s LNG gas development

by Kate DeAngelis, International Policy Analyst

Donate Now!

Your contribution will benefit Friends of the Earth.

Stay Informed

Thanks for your interest in Friends of the Earth. You can find information about us and get in touch the following ways:

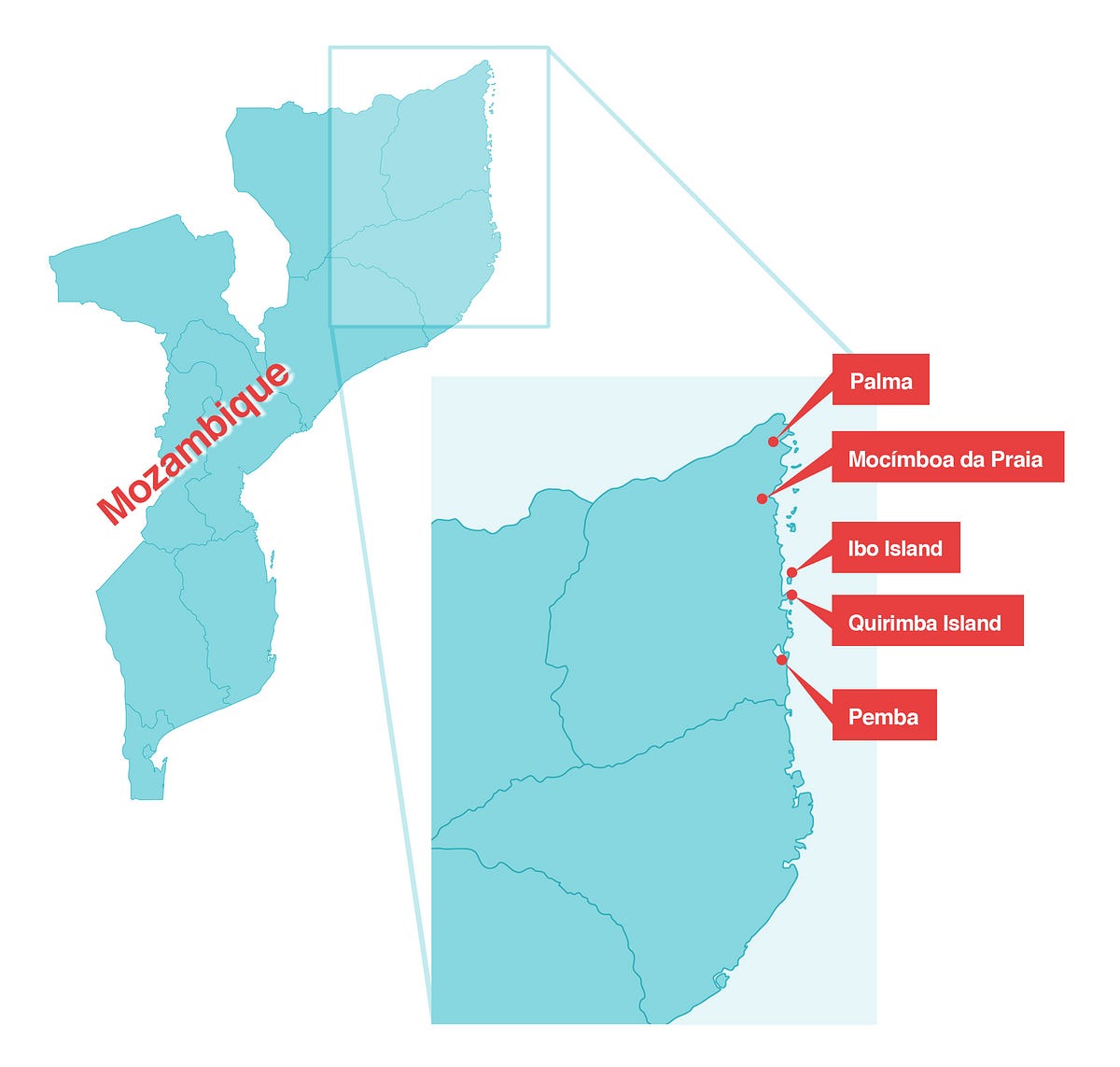

Everyone gathered underneath the central banyan tree that provided shade from the heat of the day. Not far from the city of Pemba, Mozambique, villagers clamored to tell us their stories of threats and lost land and livelihoods. This stop was the first of six villages I’d visit on my trip to northern Mozambique to conduct a field study of the impacts of the development of liquefied natural gas on rural communities and their lands. And it was U.S. government’s consideration of financing for this LNG exploitation that brought me to this tucked-away corner of the world.

The U.S. Export-Import Bank(Ex-Im Bank), the U.S. export credit agency that provides financial support to U.S. companies working abroad, is considering financing Texas-based Anadarko to develop the gas reserves. Texas-based Exxon Mobil Corp. is also very close to buying stakes in the project. The plan is: part of these reserves will be sent south via pipeline to South Africa, and the rest will be exported by large ships — most likely to markets in Asia. Aside from the many other environmental and social impacts of its development, the gas will have to be liquefied, which is an incredibly carbon intensive process, before it can be exported and then re-gasified once the gas reaches its destination. To help ensure that this financing goes forward, and these companies remain invested in Mozambique’s gas, today Mozambican President Nyusi visits Washington, D.C. and then Houston, Texas where Anadarko and Exxon are based later in the week.

Friends of the Earth U.S. is working with Justiçia Ambiental/Friends of the Earth Mozambique and the Center for Biological Diversity to discourage Ex-Im Bank from supporting this project. As a person in the U.S. working on environmental justice issues, I spend a lot of time fighting for the needs of project-impacted communities. But it can be hard to know what these people half a world away from my office in D.C. are actually going through. What is it really like to live in a place where large U.S. multinational corporations are coming in to exploit a local resource with very little thought for how this will forever change life and the potential backing of the U.S. government? What I learned was eye opening and sad but at the same time entirely expected.

These villagers are the victims of the extraction of resources required for the LNG project.

Back in the village, many people were anxious to show us their former plots of land and what had become of them. So we crammed into the bed of our rental truck. One woman brought us down a series of bumpy dirt roads to what had been her plot of land. The crops that she had planted were now withering because she was forbidden from farming there. A widow, she now has no way to feed her children. The day we spoke with her, she stood defiantly surrounded by the land she had called her own, but she did not dare harvest her crops.

We then piled back into the truck and headed down another series of dirt roads and then through the bush to what had been another villager’s plot of land. On his land now stood a recently built structure with foreigners with whom we were not able to communicate due to a language barrier. The man speculated that a Chinese company was using the land to take sand and stone for the gas industry, but the exact details and purpose of the construction remained unclear.

These villagers are the victims of the extraction of resources required for the LNG project. Included in those resources are a significant amount of sand and stone, so various companies have taken over the villagers’ land to extract the resources and build roads. The villagers allegedly have not received compensation from the companies involved or the government for their lost land. The corporations and government do not perceive the villagers as being directly impacted by the gas development.

A few days later we went up the coast to villages near Mocímboa da Praia, a city about half way between Pemba and the LNG project. One young man told us his attempts to get a job with the companies involved in the gas development. He said he had applied for jobs, such as cook and custodian positions, but was unsuccessful. He was then told that he had to pay to get on the list to even be considered, so finally he paid out of desperation, but he still was not chosen even for an interview. Then, he heard on the radio about classes teaching skills, such as cooking, that would help locals get hired by the gas and related companies. He paid to be a part of these classes, but then never heard back. It was only after payments were made in each case that he and others realized that these were scams. Local scammers have taken advantage of the lack of information provided by Anadarko and local villagers’ desperation for employment.

Some villagers who have had their land taken or destroyed are paid a small amount, but nothing sufficient to offset the lost land. In a village near Mocímboa da Praia, people showed us the forms in Portuguese they had signed accepting about the equivalent of 50 USD for the destruction of their land and agreed not to request any more compensation or complain. However, they did not realize that they had signed onto this until we explained it to them verbally because they could not read Portuguese and no one from the company had provided an adequate explanation.

Villagers are being forced to take in relocating communities, while other villagers have had their land taken for little or no compensation. At the same time, very few of the promised benefits appeared to be materializing.

We then headed further up the coast to villages near Palma, the city closest to the LNG project. Before our visit, we were not even sure we would be allowed to go to Palma. We had to alert local government officials ahead of time that we were coming and then meet with them before meeting with any of the local communities. When we met with the district officials, they took our phones away to make sure that we were not tape recording the meeting. The reason why became quickly evident, as they openly threatened us. One official said he knew who we were and that he would come after us if we caused trouble. He said that when meeting with local communities, he would know what we had said and what questions we had asked even before we had left the community. The truth of this statement because evident when an Anadarko truck even showed up at one of our meetings with a local community; the driver claimed that he just happened to be in the village at the same time.

This trip was incredibly illuminating to me in ways that I had not expected. I had thought I was going to find a vast expanse of sparsely populated land. Instead, I met many villagers who farmed the surrounding lands. So many people’s lives are being negatively impacted in different ways. Villagers are being forced to take in relocating communities, while other villagers have had their land taken for little or no compensation. At the same time, very few of the promised benefits appeared to be materializing. The situation seemed to be summed up best when a Portuguese woman working for a company somehow involved in the gas development said she was happy that the government had approved Anadarko’s proposed resettlement plan. When I asked her about the villagers that were losing their land and their livelihood, she responded, “sometimes people just have to suffer for the good of the country.”

This LNG project is toxic on many levels and is not something that Ex-Im Bank should prop up with U.S. taxpayer dollars.

In total I met with six affected communities, over 20 Mozambican civil society organizations, and 10 additional individuals. Corruption and malfeasance at so many different levels are present in this gas development, including its role in Mozambique’s secret debt. The gas development has failed to provide the jobs promised to locals and has instead led both Anadarko and supporting industries to take and destroy the land that locals depend on to support their families. Furthermore, the resettlement plan fails to think through all of the potential repercussions, including relocating one community into another of a different religion. This LNG project is toxic on many levels and is not something that Ex-Im Bank should prop up with U.S. taxpayer dollars. In solidarity with FOE Mozambique and others, we’ll be fighting to make sure that doesn’t happen.

Stay updated on this issue by following Kate on Twitter and our press releases at foe.org. Read more about this issue in the field study.