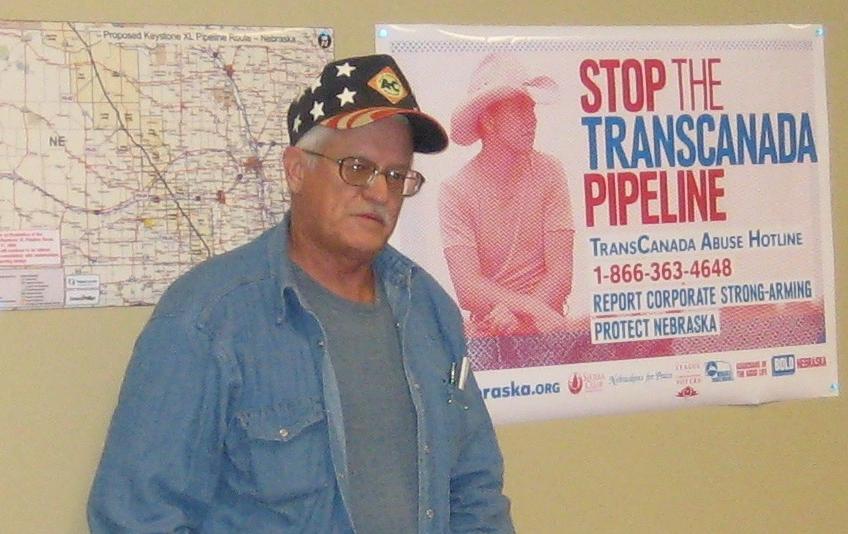

Keystone XL stories: Ernie Fellows

Ernie Fellows is a 65-year-old retired rancher living in Mills, Nebraska, a remote community that sits atop the Ogallala Aquifer along the South Dakota border. Fellows has spent his entire adult life raising livestock and tending to the land he inherited from his family. His grandfather bought the ranch in 1937, and when Ernie came of age, he was charged with taking over. “I took that to mean that I need to be a good steward of the land,” Ernie reflects, recounting the years of careful work he put into improving the ranch. However, the fruits of Fellows’ labor are under threat.

TransCanada, a Canadian oil corporation, is planning to route the Keystone XL pipeline through his property. The pipeline would carry the dirtiest oil available to the U.S. from Canada’s tar sands and bring with it the threat of contaminated water supplies and damage to property and nearby livestock. Complications have also arisen with insurance companies and lenders due to the risks the pipeline poses, making it more difficult for landowners to make ends meet.

The following is the transcript of an interview between Ernie Fellows and Friends of the Earth staff about the battle to protect his land from TransCanada and the Keystone XL pipeline.

You can read more stories from the front lines of the fight to stop the pipeline here.

When did you first hear about TransCanada’s plans to build the Keystone XL pipeline?

It was September 2008 when I first heard there was a company that wanted to come through and build a pipeline. There was a hearing in Winter, South Dakota, about 45 miles from my ranch. That was the first time any of us had heard about TransCanada or the pipeline. The next night there was a meeting in Atkinson, Nebraska. I attended and asked a lot of questions: How big is the pipeline? How much pressure is going through? How much are we going to be compensated for our land? The company said they would send out independent contractors to appraise the land — but they never even left the courthouse. They never came out to see the land.

It seems like most of the communities the pipeline cuts through are a lot like Mills — small population, mostly farm land and so on.

That’s right; I think it’s because they figure there are less people to argue with; it’s not as big a fight.

Tell me about your fight.

Two years ago I was a contractor and was partially renting out my ranch. When I heard about the pipeline I decided that I would fully rent out my ranch and stop doing contract work so I could devote myself 100 percent to fighting the pipeline.

Why is this such an important fight to you right now?

First of all, [TransCanada] couldn’t tell me what they were going to do when they abandoned the pipe. You can’t just leave a 36-inch pipe lying in the ground. My kids and neighbors shouldn’t have to deal with this problem 30 years down the road.

Second, our best chance of stopping the pipeline is before it’s started — we’ve got to do this right, right now. If TransCanada starts to build that pipe and we take them to court, the judge will just say that they already started to build the pipe, so the issue is settled. But if we can take them to court before they start building, we might have a chance.

Finally, I have issue with eminent domain. The way I see it, eminent domain is just a way for the rich guy to steal from the poor guy. If you say that you don’t want to sell your land, then they’ll just take it. This is a matter of constitutional rights. I’m guaranteed a right to the pursuit of happiness. I’m not going to be happy with that pipe going through my land. I’ll have to sell my ranch for whatever I can get and move. I shouldn’t be forced into having to make that decision.

What are the risks associated with having this pipeline on your land?

If there’s a leak around my buildings or the trees it would just wreck them — the buildings would be damaged, the trees would die, the dirt would have to be cleaned up and removed, you’d have to reestablish the sod in the grass or whatever crops were contaminated. You’d have to let the trees die or cut them down and replant. It takes three to four years for it to get dry enough to burn. Of course if they’re covered in oil they might burn really well.

The cattle drink out of a river half a mile north of the ranch. If oil seeped into the creek or the river we’d have to keep the cattle away from them. There are fish that are endangered in the river and creek that are threatened by the oil — they’d obviously die in the event of a leak. There are river habitats home to two endangered birds — a spill would destroy their nesting place. I don’t know what it would do to the deer, rabbits, pheasants, gophers field mice and songbirds like the meadow lark that all live near the river, but it wouldn’t be good.

In addition, the pipeline is a financial liability. It will be difficult to get a loan, because a spill could wreck a person’s finances. Insurance companies will be reluctant or refuse to insure the land because they don’t know who’s responsible for the pipe. If they insure the landowner and the landowner ends up being liable, well that’s a scenario insurers don’t want to touch. The easement on my property is to be 50 feet wide but if the pipeline bursts and oil shoots out at 1,400 psi it will extend beyond the 50 foot boundary. As the landowner I would then be liable but I can’t afford that kind of clean up. The oil company should be liable but there’s no hard-and-fast rule that says that they’re going to clean that up.

Finally, there’s the stress. My mother was sick in the fall of 2008 and she passed away in September of that year.I don’t think the stress of knowing this company wanted to tear up her land was helping her one bit. It pained her to know that something like this was going on. I don’t know if the stress of a leak could cause somebody to have a heart attack, but maybe it could. I wouldn’t flip out like that but I’d sure be mad.

What has the community been doing to fight the pipeline?

We’ve been holding meetings and trying to organize people to work with senators to oppose the pipeline. We’ve contacted the Sierra Club and the Nebraska Wildlife Federation for help. There has not been a lot of contact with TransCanada in the past year and a half, and we’re not sure why. In that same period of time I’ve only seen a land agent twice. I told him if he wanted to survey my land then he would have to pay to do so. He flat refused and threatened to take us to court. It wasn’t until Sen. Johanns took TransCanada on in Washington that they stopped harassing us. I think when a senator speaks up they listen.

We’re working on other avenues to take them to court on the eminent domain issue. The way that eminent domain law is written right now it gives a big company the right to come in and take your land. But they still have to prove that it’s in the public interest, and given all the big oil spills in the last year that’s difficult to prove right now.

We’re trying to introduce legislation in Lincoln that would establish liability outside the borders of an easement.

Finally, the local Natural Resource District passed a resolution banning Keystone from the area. NRD district resolutions are not the same sort of law that senators pass, but they’re binding.

Some people are just waiting for the environmental impact statement to come out and see what they do, but I’m not content to wait for somebody to come out and make a decision for me.

What does the community think of the pipeline?

The community is split. Deep down I don’t think anybody wants it, but they say they can’t fight it so they just cave in. I know two people who signed easements right away, but now they wish they hadn’t. About ten percent of the community says this is great — they say they’re getting “free money.” But that’s the problem — there’s no such thing as free money. A lot of people think that their personal property is going to benefit from the pipeline.

What has been the response from TransCanada to your organizing?

Well, I haven’t heard from anybody at TransCanda, but then again they don’t really like me. In 2009 they came out and started passing out easements. The land agent handed me what I recognized as an open end easement. I asked the agents if they were licensed to hand out easements and they told me they were. I contacted the regulatory branch in Lincoln to tell them about it and they said it was illegal because the agents weren’t residents of Nebraska. The next day TransCanada called me and told me they gave me the wrong easement and asked me to tear it up. They had given somebody else an easement and went back and scratched a whole bunch of stuff out, invalidating it. A day later the regulatory branch in Lincoln filed a cease-and-desist order against TransCanada. Three days after that TransCanada tried to take us to court, but then later declined and said they would comply with the law.

They don’t speak to me anymore.

What about the government’s response?

Some people in government seem to be helping, and some seem to be hindering our efforts. One senator insists that his constituents want the pipeline, while another senator says his constituents are split — and I tell them that they need to use a little common sense and make a decision that’s best for the general public.

There have always been some environmentalists in northern Nebraska, because of the aquifer, but we don’t call ourselves that. But then I thought about it one day and realized, “Hey, I’ve got more in common with Al Gore than I ever wanted to.”

Related Posts

Ways to Support Our Work

Read Latest News

Stay informed and inspired. Read our latest press releases to see how we’re making a difference for the planet.

See Our Impact

See the real wins your support made possible. Read about the campaign wins we’ve fought for and won together.

Donate Today

Help power change. It takes support from environmental champions like you to build a more healthy and just world.